3 Reasons (At Least) To Read “Portrait of an Unseen Woman”

Roberta Harold gives life to the story of Annie Shaw.

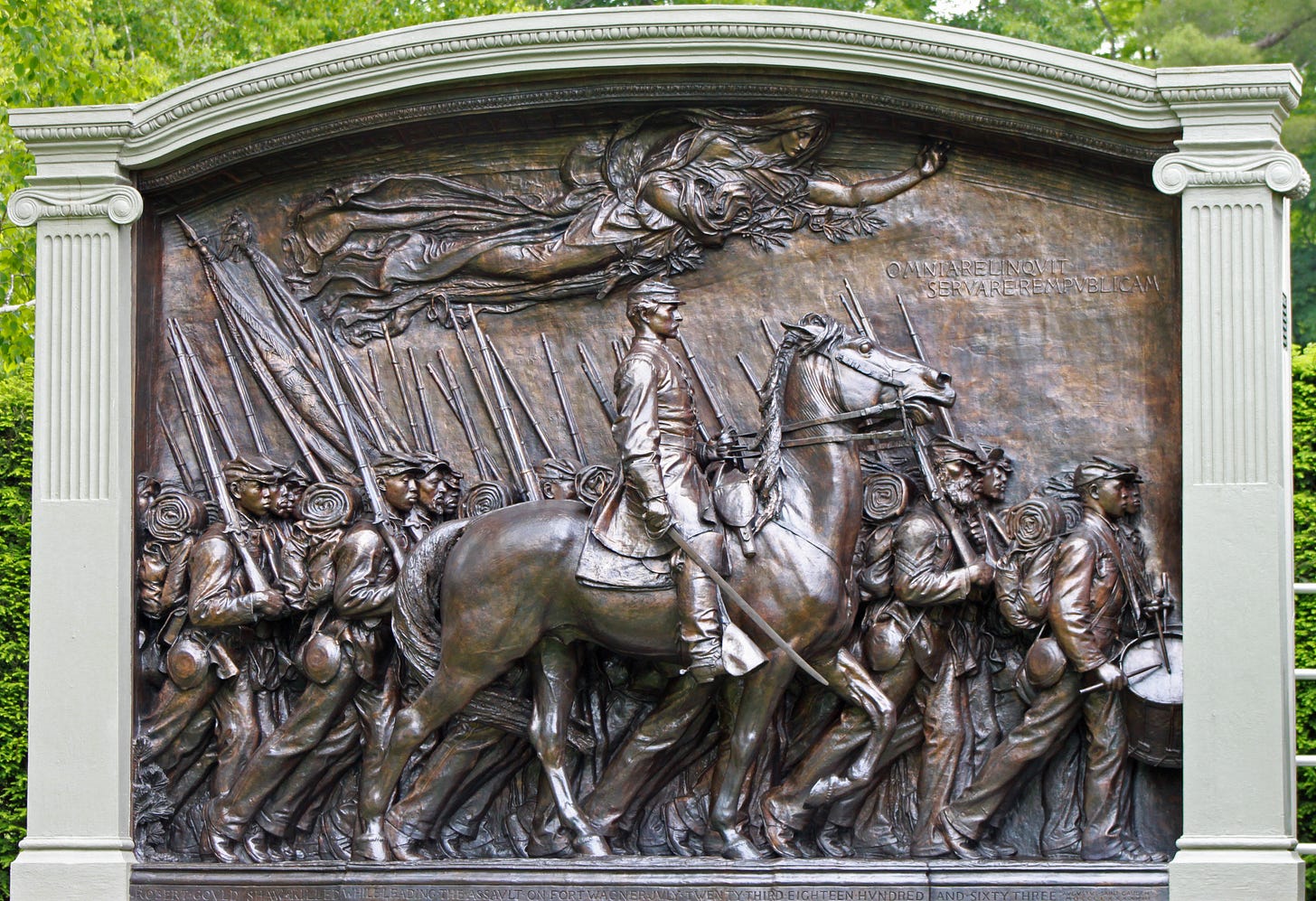

Local, and more local, ties: Have you have ever stood in front of the Shaw Memorial at Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park in Cornish, NH? The bas-relief by Augustus Saint-Gaudens is of Robert Gould Shaw, a white man from an abolitionist family, leading the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, one of the Union’s first Black regiments, into battle during the Civil War. As author Roberta Harold discovered to her (and our) surprise, the famous Robert Gould Shaw had a wife.

Her name was Annie Shaw. Portrait of an Unseen Woman is Harold’s historical novel about Annie’s life following the death of her husband, whose military career ended after he and his regiment were killed in the very battle for which he was immortalized by Saint-Gaudens. At the time of her husband’s passing, he and Anna Shaw had been married for a total of 77 days, and they had spent only 26 days together.

And, the book itself has even more local ties. Both the author and the publisher, Rootstock Publishing, are located in Montpelier, Vermont.

The book is set in the Belle Epoque period of Paris: When I first cracked this book open, I expected to meet the young widow, grieving, living in greater Boston. Annie’s story, however, is set in Paris, where she is a 56 year-old widow whose memories of her husband have thinned. Having moved overseas decades earlier with family, she is somewhat removed from the legend of her husband (whom she refers to as Rob) and likes it that way. Knowing that Saint-Gaudens is at that moment working to finish the Shaw Memorial sculpture back in the United States, Harold writes of Annie:

With the unveiling of the statue would go any chance Annie had of being seen by Boston society as anything other than the hero’s grieving widow, a role she had no wish to play any longer and, considering her first passionate opposition to his taking the regiment, one to which she’d never felt entitled.

And so, as her family is leaving to return to the United States, Annie, despite some health issues, has decided to remain and build a life in Paris, and one beyond the American ex-pat enclave. Enter people like John Singer Sargent and a cast of characters from the 1890’s world of Paris artists: painters, models, social reformers, a former suitor.

Annie’s struggle to defy social norms still resonates. Just as she has cleared her life’s runways for take-off, Annie learns that her mother-in-law is en route to Paris, and plans to live in an apartment across the hall, using Annie as her caretaker. Annie is having none of it, and concocts a scheme—elaborate and amusing—to prevent Sarah Shaw from taking root.

But why a scheme? Why not just a polite “no?” Because in contrast to the more bohemian universe to which Annie is drawn, she remains by birth a woman who is hamstrung by certain social mores that require her, unmarried and childless, to take care of others, including a mother-in-law to whom she has no attachment except dislike. The theme of women’s subservience runs through the novel as Annie finds and struggles against it in several of her relationships, including that with her own housekeeper and Carlotta, Annie’s unmarried niece. Carlotta also wants her own life but could be consigned by default to be Sarah’s caretaker if Annie breaks free.

Speaking with the author . . .

What sparked Roberta Harold’s interest and how does an author construct a narrative of an “unseen” woman? Harold responded to my question by saying she was inspired after “finding out that the otherwise excellent 1989 film Glory had excluded any reference to its hero Robert Gould Shaw’s marriage to Annie Haggerty. My indignation on Annie’s behalf energized me to dig deeply into what little historical information there was about her. I did get some clues as to who she was from letters that Shaw wrote to and about her . . .”

After amassing as many facts as possible, including a reference to Annie as being “an invalid,” Harold says: “. . . I didn’t buy the “invalid” narrative—it could mean anything in the 19th century—and as a writer and consumer of historical mysteries, I took it as a personal challenge to keep digging until I found out something that could form the germ of a story.”

“That’s my usual M.O. for writing historical fiction: something intrigues me, and then one interesting snippet of fact leads to another, rather like going up a cliff or a climbing wall and finding one more little hand-hold or toe-hold that gets you a little farther ahead. And if you’re lucky, eventually those facts connect to form the nucleus of a story.”—Roberta Harold

Since I viewed this book not just as an unearthing of a heretofore unknown part of the Shaw history, but also as a vividly rendered story of how relentlessly women need to struggle to deliver themselves from societal expectations, I asked Roberta if she thought that things had changed much for women. (Really, this could be the subject of a few dozen blog posts.) Since this book centered on caregiving duties to a mother-in-law, I chose Roberta’s words on modern day eldercare.

“Eldercare is a particularly tricky situation for women, and it works both ways. A widowed female parent may be an asset to a family with children, since she will often pitch in and help with child care and homemaking. But again, that’s an expected female role. And when the widowed mother becomes ill or disabled, it typically falls to the daughter(s) to provide the care she needs. The “sandwich generation,” which refers to middle-aged people caring both for young children and elders, is typically a squeeze for its females, not its males.”

Portrait of an Unseen Woman is a great read—lively, funny, and picturesque in its portrayal of Belle Epoque Paris. It is also one more step forward in bringing women’s stories to light, particularly like that of Annie Shaw whose very presence—despite the historic prominence of both her husband and the famous artwork it engendered—went unnoticed. Kudos to author Roberta Harold for her sleuthing skills and her imagination. More, please.

(Shop local! This book is on the shelves at the Norwich Bookstore and Still North Books and Bar.)

——————————————

Thank you! You’re reading Artful, a blog about arts and culture in the Upper Valley, and I hope you’ll subscribe (still free) and then share this post with your friends and on your social media. We have 3200 subscribers.

And in case you are wondering . . . Susan B. Apel shuttered a lifelong career as a law professor to continue an interest (since kindergarten) in writing. Her freelance business, The Next Word, includes literary and feature writing; her work has appeared in a variety of lit mags and other publications including Art New England, The Woven Tale Press, The Arts Fuse, and Persimmon Tree. She connects with her neighbors through Artful, her blog about arts and culture in the Upper Valley. She’s in love with the written word.